Can trees save the planet? Writer and amateur botanist Robert Langellier digs into the realities of what it means to have forests—and to lose them.

Can trees save the planet? Writer and amateur botanist Robert Langellier digs into the realities of what it means to have forests—and to lose them.

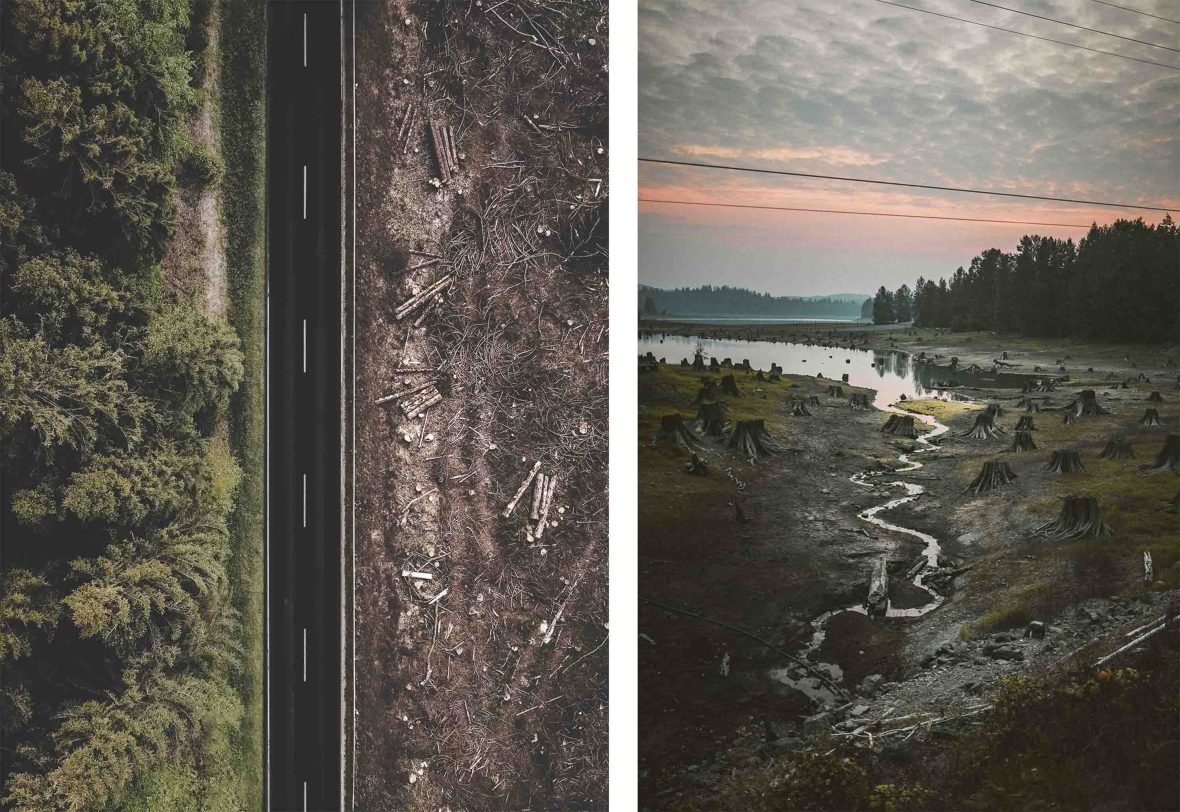

I spent much of summer 2021 driving seemingly every numbered roadway in western Montana and northern Idaho, identifying plants in remote streams for the United States government. The goal was to untangle how cattle grazing on public lands affects stream habitats that had once been old-growth forests before clearcutting (a controversial logging method in which all trees are uniformly cut down) in the 20th century. I could convince myself, then, that in a very indirect way, I was playing a tiny role in protecting old-growth forests.

That optimism self-moderated as I drove extensive panhandle roads through clearcut forests, without a single standing tree in sight. The Rocky Mountains of northern Idaho are one of the most undeveloped and forested areas in the US, making it the perfect place to hide extensive forest degradation. Previous work as a wildland firefighter in California gave me a startling view of apocalyptic, burnt landscapes. On the long drives in Idaho, I considered the extent of deforestation around the world.

Truthfully, even most professional botanists and land stewards have little sense of deforestation at the global scale. I had simple questions: Who are the major players in deforestation? What are its real causes? How bad is it really? And can we grow our forests back?

A quick note on vocabulary: One quickly learns there’s a difference between “deforestation” and the more ambiguously worded “forest degradation.” One learns more slowly what that difference means. Contained within “deforestation” is the permanent clearing of large timber tracts for the purposes of grazing and plant agriculture, as well as urban development and roadways. “Forest degradation” describes plantation logging, wildfires and small-scale clearing for subsistence agriculture in developing countries, which may not be as permanent as large-scale commercial agriculture. Some things, like logging virgin redwoods in the American northwest or wildfires that consume entire forests and burn the soil at high severity, lie in the opinion section of the spectrum. Statistics are as imperfect as reality. I consider both to be net negative—more bad than they are good, that is—with an inclination to meld together.

In the present day, I work in landscape restoration, which relies on some data and a lot of educational guessing about what our planet used to look like before we wrung it out. Best estimates say that, at the turn of the last ice age, 57 percent of the inhabitable earth was forested. Now it’s 38 percent. Shrub- and grasslands have declined much more dramatically. In their place is five billion hectares of ranch land, agriculture and city. Of those, only one percent is urban development. The vast majority of deforested land consists of grazing and cropland.

What forest loss means to you depends partly on your latitude. In North America and Europe, the majority of modern forest loss is the result of wildfire and logging. In tropical regions, deforestation for grazing and farming dominates. And wildfires are ramping up. The US lost three times as much forest to wildfire in the last decade than it did from 1983 to 1992, when records began. But the American temperate forest, vital as it is, isn’t in the global crosshairs.

The modern story of forest loss can largely be told by two countries: Brazil and Indonesia. Fran Price, the forest practice leader at the World Wildlife Fund, points out that it makes more sense to identify regions, not countries, with high deforestation rates. Still, these two countries alone account for almost half of all modern deforestation, about 2.3 million hectares per year—largely felled for cattle, soy, palm, and paper and pulp production. As soon as former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro took office in 2019, destruction of the Brazilian Amazon increased 88 percent, while unprecedented wildfires ripped through the region.

But that story is misleading. As Dr. Toni Lyn Morelli, a research ecologist at the Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center, points out, “It’s important to not be blaming the people left with meager resources by saying they’re destroying everything. In Europe, we don’t complain about deforestation because so much of it is already gone.” When looking at modern leaders in deforestation, one might ask why so much of the surviving global forest is found in developing regions.

Perhaps surprisingly, in 1990, for the first time in modern history, temperate forests started gaining more cover than they were losing annually. This is not true even remotely for tropical forests. If you are a pessimist, you will note that the tropics lost 53 million hectares in the last decade. If you’re an optimist, you’ll point out that the trend is moving in the right direction. The rate of loss has decreased at an unbelievable pace since the 1980s. The tropics, including in Brazil and Indonesia, are now losing one tree for every three lost in the ‘80s. One might take solace in dying more slowly than ever.

Statisticians have consolidated this into a fascinating bell curve story. According to the “forest transition model,” modern nation-states follow a general deforestation trend. As a country industrializes and develops, it consumes its forest exponentially, due to a growing need for resources and agricultural land. Eventually, however, it reaches peak deforestation—and as the population growth slows, agriculture becomes more efficient per hectare, and wood fuel gives way to fossil fuels or renewables, the trend starts to reverse. Today, the United States, Russia, China, India and virtually every European nation is actually gaining more forest than it’s losing. Scotland, which cut three-fourths of its historic forest by 1870, has regained nearly all of it.

“If we do environmental restoration poorly—and there are plenty of examples of that—then actions that are taken in the name of environmental restoration are instead going to deepen social inequality, destroy habitats and exacerbate climate change.”

- Leighton Reid

At its current pace, Brazil might begin gaining tree cover in a few decades—which should not be confused with rainforest, which in many cases cannot return once lost. Price says a third of the country has already crossed several tipping-point thresholds in the last decade: Rainfall, length of dry season, and deforestation. At a certain point, without a course correction, deforestation and climate change will send the Amazon into a biome type-change at a continental scale—meaning that the Amazon will no longer be a rainforest.

“Rainforests create their own ecosystems in this amazing way,” Morelli says. “A lot of rain that comes down is kept in the system and recycled. When you start fragmenting the forest, it gets more and more sun exposure, dries out, and the weather patterns change. Then you don’t have a rainforest anymore.”

The outlook is bleak, but at least in Brazil, Bolsonaro is out of office now. “There’s a spirit of optimism now that hasn’t existed in the last four years,” says Price.

But let’s go one layer deeper. I eat chocolate from West Africa and palm oil from Southeast Asia. The US, like all developed nations, imports deforestation from other countries, meaning that just because my country is reforesting doesn’t mean our net balance is positive. Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser from online scientific publication, Our World in Data, compiled UN Food and Agriculture Organization data into a graph that adjusts reforesting countries against “imported deforestation.”

Germany, for example, consumes so many goods produced by overseas deforestation that they’re effectively starving the world of forest, regardless of what’s happening on their home soil. Combined, Germany and Spain added 3,170 hectares of forest to their land while importing the equivalent of 76,000 hectares of deforestation abroad.

By contrast, China, the US and Australia are still way in the clear, even with the adjustment. China, especially, is adding eight times more forest than it’s depleting elsewhere. But let’s go even further. Syria’s ratio is almost perfectly 1:1. Cutting forests in the Middle East or second-growth woods in France, however, does not equate to the same biodiversity or carbon loss as cutting forests in the Amazon.

It feels wrong to call one latitude of forest more important than another. But by almost any metric, the tropics trump the temperate and boreal forests. Saliently, tropical forests sequester (capture, remove and store) more carbon and contain unparalleled biodiversity. In 2020, Morelli co-authored a study published in science journal Nature that found that Madagascar’s rainforest will effectively be deforested by 2070 at current trajectories. “It’s hard to say things like, ‘there will be no more rainforest in 50 years.’ It just sounds like you’re lying, because it’s such bad news. Nobody wants to believe it,” Morelli says. More than four percent of the world’s biodiversity is only found on the island of Madagascar. Its rainforest covers an area about the size of Switzerland.

Not all woods are created equal, and that can’t be graphed.

It’s a hard sell to cut native trees, which is virtually all I do for six months of the year. My crew and I are no loggers; everything we cut, we burn or let decay. In my region in the central US, disturbance patterns or fire suppression have left a landscape so thick with trees that it’s choked biodiversity. Eastern redcedars, especially, have taken over much of our native grasslands, where they historically didn’t grow.

In the Boston Mountains of Arkansas, unmanaged thickets of red and white oaks consumed too many soil nutrients for what that level of tree density could handle, causing widespread oak decline at the hands of oak borer insects in the late 1990s and early 2000s. One might call it too much of a good thing.

I frequently clearcut eastern redcedars off historic glades, a dry grassland habitat home to specialist grass, wildflower, bird and insect species.

In the last decade, tree planting around the world has gained tremendous momentum, with the catchy hypothesis that planting a trillion trees could reverse the effects of climate change. Nature abhors that kind of simplification.

“Nature is complicated,” says Dan Drees, a fire ecologist with the National Park Service. “If we just let the trees overrun the glades and prairies, there might be some carbon sequestration benefits to a small degree, but at a cost to biodiversity; and not just species, but whole systems that no longer function because they evolved with historic fire regimes that trees weren’t a part of.”

I clearcut my first glade in 2018. I return each summer to see it. Now it’s a vibrant eight-hectare grassland filled with delphiniums, rose verbena, hyacinths, prickly pear cactus, milkweed and lady’s tresses, crisscrossed with butterflies. Not all woods are created equal; some, perhaps, shouldn’t exist.

In the last decade, tree planting around the world has gained tremendous momentum, with the catchy hypothesis that planting a trillion trees could reverse the effects of climate change. According to a 2020 analysis in the journal Nature, forests make up about half of the total terrestrial carbon sink (land that is able to capture carbon from the atmosphere). Forests in the tropics contain about seven times as much carbon as we emit each year, meaning they have tremendous potential if we maintain them and tremendous consequences if we remove them.

For all the benefits of the ‘Trillion Tree Campaign,’ nature abhors simplification. Tree plantations are closer to gardens than ecosystems, and they sequester less carbon than natural forests. The earth naturally grows its own trees better than we can—areas where we have to force trees into existence are likely areas where they’ll be recut for timber or agriculture. Forest tunnel vision can cause us to plant over grasslands, savannas and peatlands, which are oft-threatened biodiversity and carbon strongholds.

Sometimes we plant exotic trees like eucalyptus and radiata pines in ways that ravage local ecosystems or suck up water vital to nearby communities. In boreal regions, trees often actually warm the earth, as solar radiation is absorbed through dark green needles instead of reflected by snow. And in a darkly comedic way, many tree-planting campaigns focus on planting, not monitoring, meaning a huge number of planted trees are subsequently ignored and left to die.

“How and where we restore the environment just in this decade is going to have huge implications for the future of life on earth,” says Leighton Reid, an assistant professor at the Virginia Tech School of Plant and Environmental Sciences who studies restoration ecology in the tropics. “If we do environmental restoration well, we can improve billions of livelihoods, prevent thousands of species extinctions and sequester enormous amounts of carbon. The trade-off is that if we do it poorly—and there are plenty of examples of that—then actions that are taken in the name of environmental restoration are instead going to deepen social inequality, destroy habitats and exacerbate climate change.”

At the individual level, your options for fighting global deforestation are limited, but not zero. The refrain of cutting down on beef and dairy is, indeed, your single best way to help. Fran Price also points out that 40 percent of food is lost between the producer and consumer, much of it at home, so reducing food waste goes a long way. There’s also good old-fashioned donating. “If you want to give money to a tree-planting cause that you know is going to be good, then you might look at some local organizations that you can contribute to directly,” says Reid. By “local,” he means groups that are of and a part of the local ecosystems they’re restoring. “One of the ones I work with closely is Green Again Madagascar, farmers in eastern Madagascar growing local Malagasy trees with their neighbors.” Consider that preserving standing forests is always better than planting new ones, and tropical forests are more vital to global systems than temperate or boreal ones. But of course, we need them all.

In November 2018, I was loaded into a van stuffed with dirty, adventuresome Americorps members and shot down Interstate 10 to deep south Texas, 30 miles north of the border at McAllen. La Sal del Rey was 100 hectares of abandoned farmland surrounding a salt lake.

For a month, we were to follow behind an auger attached to a large tractor, which drilled holes in perfect eight-foot increments. With aching, then dulling, backs and knees, a crew of 30 planted 42,000 spiny Tamaulipan thornscrub species in a golden sea of cowpen daisies and invasive grasses. In my memory, one young man sang ‘Big Rock Candy Mountain’ nearly the entire time.

The thesis was that 42,000 shrubs and trees would restore habitat for ocelots native to the border region. They would also capture more carbon than the horizon of daisies. That restoration site at La Sal del Rey is nearing five years old now. I’m told that feral hogs dug up a lot of the seedlings before they established. But some of the three dozen species we planted, like the thorn-ridden blackbrush acacia, took off and flourished. The project lives where most projects do, between success and failure. Nature finds the balance. Not every tree planted will become an old-growth redwood. But planted thoughtfully, a twisted blackbrush acacia will keep the soil where it stands from washing away. It will provide nectar for bees and butterflies. It will play its part where it belongs.

Robert Langellier is a freelance journalist, amateur botanist, and landscape restoration worker based in the Missouri Ozarks. His work has appeared in Esquire, National Geographic, and The Nation. In the past, he has worked as a wildland firefighter on a hotshot crew in California and as a long-haul truck driver, as well as a translator.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: