Karakol might be known as the adventure capital of Kyrgyzstan, but writer Samia Qaiyum finds herself on the receiving end of a much more cultural—and surprisingly delicious—experience.

Karakol might be known as the adventure capital of Kyrgyzstan, but writer Samia Qaiyum finds herself on the receiving end of a much more cultural—and surprisingly delicious—experience.

Ibraim is meticulous in his handling of a specialty drip coffee bag, proudly revealing that he scored a boxful on a recent trip to Moscow. He’s a friendly guide and insists that I join him for a cup, but I hesitate. I’m tempted, but the rainy weather is relentless, each gust of cold wind a reminder that any beverage I consume will inevitably trigger a call of nature—with nowhere to answer it.

We’ve stopped for a picnic-style lunch in a big grassy field a few miles outside of eerie Engilchek, a once-thriving mining village of 5,000 that’s now a ghost town—poised high in the mountainous Issyk-Kul Region of Kyrgyzstan. Ibraim assures me that a cup of coffee won’t hurt. The language barrier is undeniable, but his advice essentially translates to, “If you have to go, just go.” I reply by awkwardly using hand gestures to point out that for men, unlike women, the whole world is a bathroom. His colleague, the burly ranger responsible for today’s arduous drive from Karakol, chuckles with amusement as he slurps his tea. I’m mortified, but my embarrassment is a small price to pay for the opportunity to be here.

What follows is three hours of dark tourism bliss as Ibraim and I walk among the decay, debris, and phantoms of Engilchek. At one point, I’m convinced that I’ve actually captured them on film until I realize it’s just a couple of raindrops on my camera lens adding a suitably disturbing blur to my images. The likes of weathered newspapers, empty cigarette packs, bird nests, and even a goat jawbone are accompanied only by a deafening silence. Anything of value has long been stolen, but I feel like I’ve found a long-lost relic when I stumble upon a crumpled, sepia blueprint. It’s a tangible remnant of the Soviet Union’s presence, depicting plans for an underground mine just waiting to be exploited — and a reminder of how Russians quite famously benefited from the wealth of minerals in the vicinity while the Kyrgyz miners lived in lousy conditions.

Standing here among broken masonry, I’m grateful Karakol is my base to explore Kyrgyzstan as opposed to the capital of Bishkek. Karakol is most often used by tourists as a hub for recreation—to access the remote and rugged Tian Shan mountains, hike, ski (in fact, Karakol Ski Base is Central Asia’s highest ski resort), ride horses, and kayak. Although tourism has been a slow-growing industry for Kyrgyzstan (according to the Library of Congress Research Division, an average of about 450,000 tourists visited annually in the early 2000s, mainly from countries of the former Soviet Union), the focus in the last handful of years has been adventure travel.

In 2018, the British Backpacker Society ranked Kyrgyzstan as the fifth-best adventure travel destination on earth, and an adventurous secret “bound to get out soon.” National Geographic alluded to the recreational attractions around Karakol being miraculous in comparison to the region’s cultural depth, publishing, “In the cities of Kyrgyzstan there are many Soviet-style buildings, spacious markets and colorful mosques. However, outside of Bishkek and Osh you will see a miracle—high-mountain lakes, snow-capped peaks and walnut forests.”

Karakol is small—the population is only around 84,000. But for as small and relatively young as it is, it’s also historical, complicated and dynamic.

For these travelers, Karakol is a gateway—to enter the mountains or return from them. Instead, this is where I’ve slowed down, relishing the fact that it’s easily explored on foot and full of unsung cultural treasures.

Karakol is small—the population is only around 84,000. It was founded as a Russian military outpost in 1869 and has a long history of military presence, Soviet occupation, and, of course, emancipation. It is home to Dungan, Uyghur, Kalmak, Uzbek, Russian and Kyrgyz people, an Islamic mosque, a reclaimed Russian Orthodox cathedral, and museums that unflinchingly display Indigenous petroglyphs alongside Soviet-era perspectives. For as small and relatively young as it is, it’s also historical, complicated and dynamic.

That’s not to say that it’s more convenient than visiting someplace else in Kyrgyzstan, like Bishkek. Incidentally, this region grew in the 1800s after Russian cartographers came to map the peaks and valleys separating Kyrgyzstan from China. The ghost town of Engilchek is located in a 30-mile buffer zone near the border with China, which means that access is restricted. A permit to be here is not only mandatory but also scrutinized alongside one’s passport at a preceding military checkpoint (which I’ll remember for the Mongolian camels casually hanging around). My permit was arranged by Ibraim’s team at Visit Karakol, a process that first piqued my curiosity about what the city has to offer.

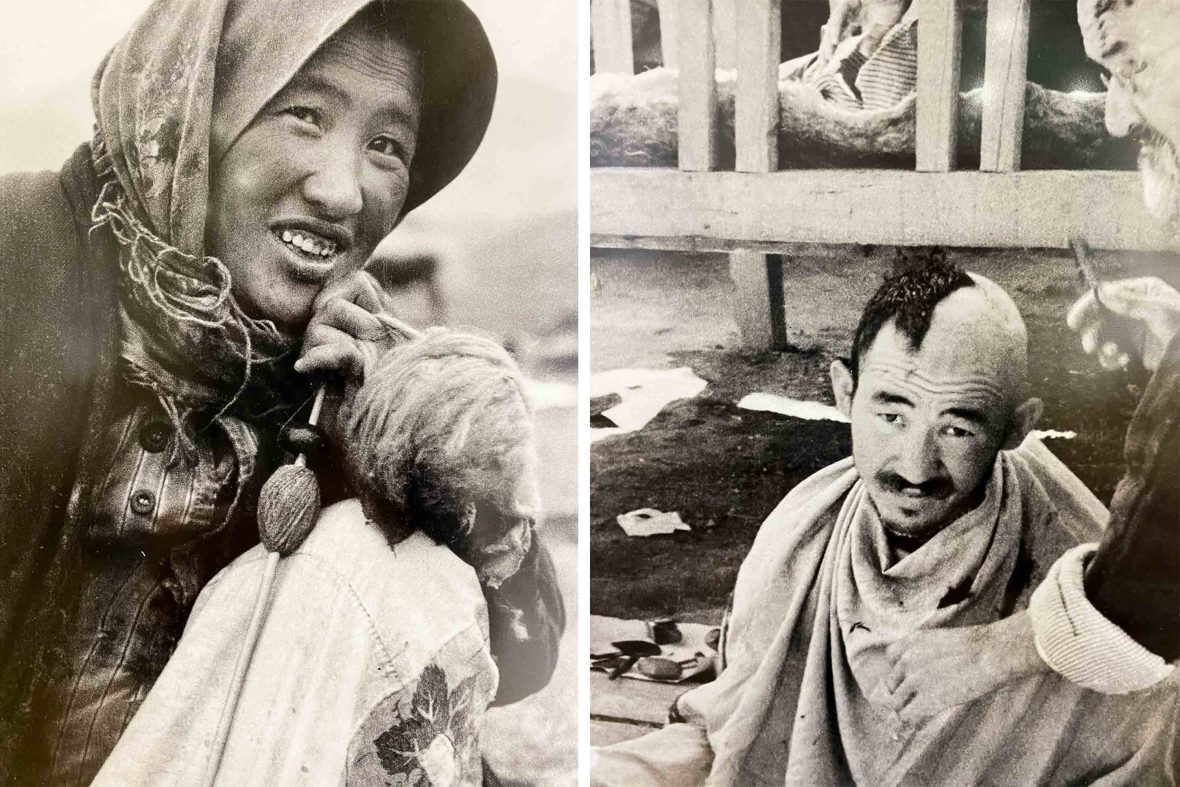

A chance encounter with the late Ella Maillart in the back of Karakol History Museum affirms. The Swiss explorer was the first woman widely documented to travel alone across the lands of Central Asia. Here, her adventures are immortalized through a permanent photography exhibition. Maillart’s black-and-white photos are downright gripping, her lens transporting viewers back to everyday life during her 1930s expedition through seemingly mundane street scenes—back before the region fell under the Soviet Union’s reign. Back when life was arguably more wholesome. There’s the young kebab vendor who smiles as he juggles multiple skewers of meat. The chador-clad women lined up to sell embroidered caps to men. A glimpse inside a nomadic doctor’s yurt. A mare being milked in anticipation of kymyz (a foamy, fermented beverage that’s still hailed as a cure-all).

I’ve paced myself on this trip, repeatedly pausing to photograph the details of the wooden ‘gingerbread’ houses in Karakol’s Russian quarter. These serve as lasting symbols of the days when Karakol was a Russian settlement inhabited by wealthy merchants, called Przhevalsk then. The turquoise shutters and intricately carved facades pair perfectly with the surrounding nature—ash and chestnut trees in the foreground, snowy peaks in the background. It’s just askew of a fairy tale. Elsewhere, shades of blue adorn another prominent structure—one where I felt incredibly welcome. I find myself in the city’s Dungan (Chinese-Muslim) community, offering a stark contrast to the emptiness of Engilchek.

“They’ve simply accepted that it’s a part of their story,” she replies with a shrug. A wave of sadness crept in as I reflected on how little has changed all these years later.

I start with an afternoon at Dungan Mosque, built by Chinese artisans between 1907 and 1910. Not only was it ingeniously constructed (there are no nails, owing to financial limitations), but it also reflects unforgotten Buddhist roots. A pagoda in place of a minaret. Wooden pillars are decorated with images of plant life and fruits. Everything about its architectural ambiguity intrigues me, evident in my gait until I was abruptly stopped by an elderly, bearded gentleman near the entrance. The next few seconds are a bit of a flash between being charged a 20-som entrance fee before being asked what religion I follow (Islam), then my money finding its way back into my hand as the man flashes an earnest grin that reveals barely five or six teeth.

Hours later, an early dinner in the home of a Dungan family elicits mixed emotions—the backstory of this community admittedly hits a nerve. Fleeing persecution in China, their ancestors escaped in the 1800s, arriving in Kyrgyzstan via the dangerous Torugart Pass in the Tian Shan mountains. Thousands died of cold or starvation, but the Dungans who survived made Karakol their home—and diversified its culture and cuisine in the process. I asked a translator if modern-day Dungans feel a sense of resentment towards China. “Not really. They’ve simply accepted that it’s a part of their story,” she replies with a shrug. A wave of sadness crept in as I reflected on how little has changed all these years later. Look at the rising Islamophobia in India. Or the proposed hijab ban in France. Or the ongoing repression of Uyghur Muslims in China.

Still, this last night is about celebrating a journey from tragedy to triumph. About discovery and dynamism. We dig into an absolute feast of seasoned salads, steamed buns, bowls of rice, and hand-folded dumplings that fill the tables of our humble dining hall. Ashlan-fu was the star attraction. Once my palate made peace with the fact that this beloved noodle soup is served cold, I appreciate its complexity. Sour, tangy, and gloriously spicy—a new favorite. I silently vow to make a pit stop at the eponymous Ashlan-Fu Alley in Bugu Bazaar before I go. One more bowl beckons, after all.

Samia Qaiyum is a Dubai-based editor who specializes in travel and culture. She contributes to Elle Arabia, Vice Arabia, National Geographic Traveller, and Condé Nast Traveller. A textbook third culture kid with a perpetual thirst for adventure, she has lived in five countries and traveled to 34 others, racking up all sorts of weird and wonderful experiences along the way.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: