He’s hitchhiked alongside eccentric filmmaker John Waters, spent time with the men who cremate bodies on the Ganges, and eaten a still-beating snake heart in Vietnam. Veteran travel writer David Farley shares how anyone can come back from a trip with a tale to tell.

I once went hitchhiking with American film director John Waters. After we were picked up down the street from his Baltimore home, he looked back at me from the front seat and smiled and gave me a quick nod, as if to say, See, isn’t this fun? And then, perhaps to justify his fondness for hitching rides, he said, “I think it’s dangerous to stay home. Never going out and seeing the world and meeting new and interesting people? Now that’s dangerous.”

I couldn’t have agreed more. I’ve done some things that might appear crazy to people who don’t get out much. I’ve hiked across small European countries. I spent two weeks hanging with men who cremate bodies on the banks of India’s holy Ganges River in Varanasi hoping to glean some secrets about life and death. I’ve eaten a still-beating snake heart in Vietnam. I’ve gone in search for a strange holy relic in Italy, placing me face-to-face with not-so-thrilled Vatican officials.

And I did these things under the guise of ‘travel writing,’ but really, I do it simply because it gets me out of the house, onto an airplane, and to parts of a place I’d never normally wander. As a result, I’ve been transformed by every trip.

I make connections with friends of friends on social media. Facebook is my go-to channel because it’s the most interactive and where I’ve had the most success in connecting with other people.

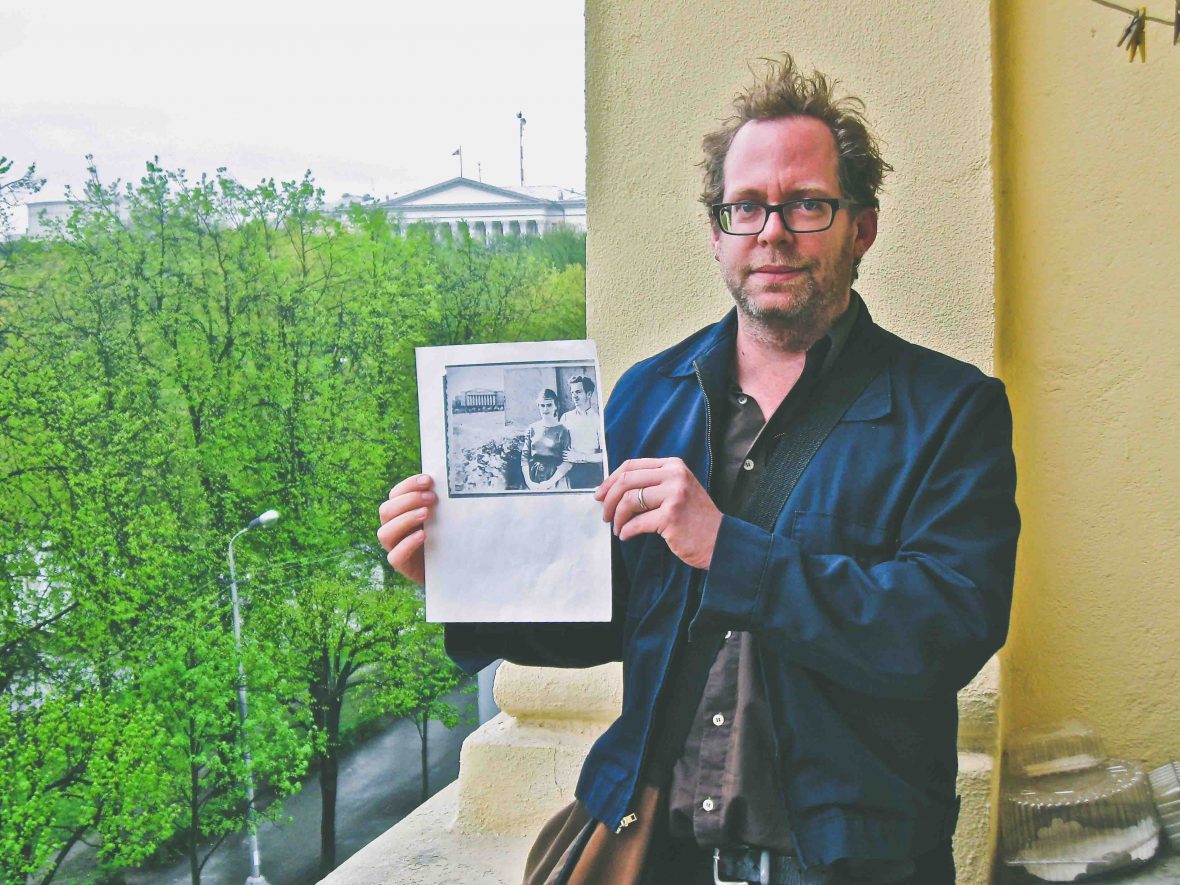

For a travel magazine assignment, my editor wanted to write me a feature on Minsk, Belarus. But there was only one problem: “You don’t know anyone there, do you?” he asked. “We really like our writers to be as immersed in the culture as possible.” I made him a promise: I’ll make so many connections, I’ll even have people picking me up at the airport.

Sure enough, a group of locals were waiting for me when I landed in Minsk. That same group of people, all musicians and artists, also ended up making great sources for my story and, in turn, became friends too. In the end, I got to see and write about a side of Minsk that I wouldn’t have experienced had I not been forced to make connections with locals. The knowledge a local can disperse about her or his city goes far beyond anything a guidebook can tell you.

Many of us travel to a place to see something we’ve always wanted to see. We have this gravitational pull to view it with our real eyes. But travel writers have to see a place differently; if we just kept covering the Pyramids of Giza, Machu Picchu, and the Taj Mahal, travel journalism would no longer exist. So, I often end up going to spots to write stories that seem counter-intuitive to our knowledge of the place.

Some of my well-traveled friends were dismayed when I told them I was going to the south and the west of Ethiopia, for example. “Why even go to Ethiopia if you’re not going to see the underground churches in the north?” was the common refrain. That I was going to hang out with coffee farmers received mostly perplexed stares in response.

Other examples, include going in search of hardcore local bars in Dubrovnik and spending time on a Greek island not to sunbathe but to volunteer at a refugee camp. By literally and figuratively going down a different road in places around the globe, I’ve challenged myself to see a different side of the world and a different side of myself.

As I see it, travel writers have a duty to go beyond the orbit of the average tourist, to push through the center-of-town masses and roam to an imaginary precipice. My job is to say ‘yes’ to all offers while on the road, even if I don’t know where that affirmative will take me.

One of my most memorable experiences happened on assignment for a story on Bolivia. While walking around La Paz, the Bolivian metropolis set in a large bowl 12,000 feet up in the Andes mountains, a group of beer-guzzling Bolivian local women beckoned me over to the curb where they were stationed. I had no choice but to say “sí.”

Within seven seconds, I had a plastic cup of beer in my hand and we were toasting—although I was reprimanded for not spilling my beer on the ground before taking a sip. “You must honor Pachamama,” commanded one, referring to the Andean mother earth goddess. For these women it was a leisurely Saturday of drinking and spilling beer—err, honoring the goddess—while catching up. For me, it was an unforgettable travel moment.

There’s so much talk about how travel changes people; social media often broadcasting that oft-quoted Mark Twain line about how travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry and all those other traits we abhor. Well, this is true. Sort of.

We move from place to place, from point A to point B, with the idea that just this very movement, this very act of getting out of our daily routine, will bring us more contentment in life, a temporary reprieve from the ennui of our daily routines. But travel only changes us if we are open to being changed by it.

One quote that I often let guide me when I’m traveling is from George Bernard Shaw: “I dislike feeling at home when I’m abroad.” Globalization has made the world less distinct, meaning we have to try harder to wade through the familiar sights, such as the multi-national shops and stores that are now fixtures in nearly every city center on the planet. If you want to see something unique to the place, we now have to explore.

Maybe one of the problems with modern travel is that we tend to do it with a material aspect in mind: That the nicer the surroundings, the more luxurious it appears, the better. But this doesn’t always give us the most satisfaction. After all, luxury has a way of infantilizing us. Not that there is anything wrong with planting yourself in a five-star hotel once a while. But if that’s the only way you travel, then you’re missing most of the world.

Once we take that step out of our comfort zone, something else happens: We open our hearts and minds to a destination; we throw down our guard; render ourselves vulnerable. We drop the ego.

Prince once crooned, “The only love there is, is the love we make.” This is true. But in terms of travel, “The only path there is, is the path we make.” So, in these days when fear and xenophobia are threatening to knock down all the global goodwill we’ve tried to build, it’s never been a better time to heed John Waters’ words, get out of the house, and carve a path somewhere on the planet in the name of love and understanding.