Editor’s note: This article was published before the coronavirus pandemic, and may not reflect the current situation on the ground.

In 2011, a devastating earthquake and tsunami struck eastern Japan. In the city of Kamaishi, buildings were swept away and over a thousand people perished or disappeared, and in its rebuilding, the city chose to prioritize a rugby stadium. Former rugby player Ash Bhardwaj went to find out why.

“We don’t say ‘we survived’,” says Iwasaki Akiko, “We say ‘life is given to us.’”

I’m standing next to Houraikan, Iwasaki’s ryokan or traditional Japanese inn. In front of it, a line of trees sit atop a sea wall, which drops five meters to a narrow beach and into the still water of a Pacific bay.

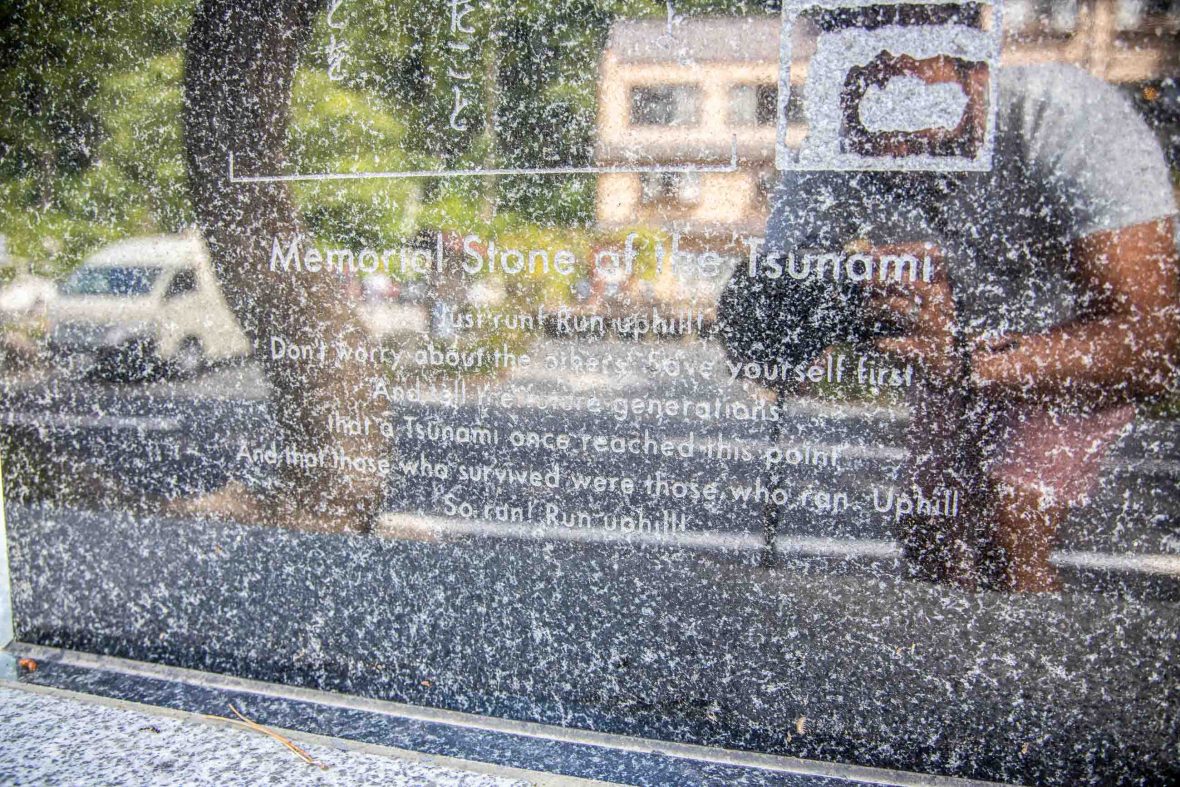

But I’m looking at a red line on the inn’s second storey. It shows the high water line of the 10-meter tsunami that crashed over the wall and submerged the inn on March 11, 2011. Behind it, a path climbs steeply up the wooded mountain, passing a stone pillar dedicated to a Japanese god of water.

“That was the path we escaped up,” Iwasaki says, smiling all the time, “The building survived the tsunami and, when the water receded, we became a shelter for people who had lost their houses. In times like this, every person has a position, a role to play—just like in rugby.”

Houraikan is on the same bay as the new rugby stadium, Kamaishi Recovery Memorial Stadium. The sport has a long history here: Back in the 1970s, when professional rugby first came to Japan, Kamaishi’s local team won seven national championships in a row. Sponsored by Nippon Steel, and considered unbeatable, they became known as the ‘Iron Men’.

RELATED: The incredible life and times of Japan’s most influential artist

“Rugby is Kamaishi’s spirit and history,” says Yuta Nakano, the current captain of Kamaishi Seawaves Rugby Football Club. “Because of that success in the 1970s, everyone in Japan over the age of 50 knows of this city. There are Kamaishi fans all over Japan, and I’m grateful to play for a city with such a proud rugby heritage.

“After the earthquake, people wanted us to play, to cheer them up and distract them,” he continues. “The damage meant we had to go to Morioka or Kitakami to play our home games, but now we are playing in Kamaishi again.”

Shane Williams is one of Wales’s greatest-ever rugby players, with 300 international points to his name. He played club rugby in Japan in 2012, and is going back as a TV pundit for the Rugby World Cup, covering the games in Kamaishi.

“The Japanese love a festival,” he tells me when I meet him in London. “And it doesn’t get bigger than the World Cup; visitors will be overwhelmed by the enthusiasm. I remember playing against Kamaishi, when they were still playing in Morioka. They were so proud of their city, and the values of rugby—sacrifice, commitment, community and patience—are the characteristics of the people of Kamaishi.”

I ask him if he thought the stadium was worth it.

“Well, I’m going there for the games, along with tens of thousands of other people. And millions will see Kamaishi on television and know its story. If they hadn’t built the stadium, none of that would be happening.”

The walk to the stadium is lined with enthusiastic volunteers welcoming me with high-fives. The stadium itself has no roof, giving everyone a fantastic view of its setting. It has to be one of the most spectacular in the world: The ocean in one direction, forest-covered mountains everywhere else.

RELATED: What’s the magic ingredient in Japan’s Alpine cuisine?

The game ends with Japan defeating the gigantic Fijians, who are also reigning champions in the Pacific Nations Cup. It’s an auspicious start for the new stadium, and one worthy of celebration, so I head to Kamariba, Kamaishi’s izakaya (pub) district of narrow streets, red lanterns and the smell of good food.

“Kamaishi is known for three things,” says the man sitting next to me in Yoshi-Yoshi restaurant. “Steel, rugby and seafood. Most of the steel industry is gone, but the rugby is back, and this is the best place for seafood.”

As Mitsutaka prepares to leave, a group of locals, who have overheard our conversation, ask if he was really spending 14 hours on a bus, just to volunteer at a rugby game. He modestly nods an assertion.

They thank him deeply, and then gave him a standing ovation. Embarrassed at the attention, he bows whilst backing out of the izakaya, as the applause continues.

It strikes me, then, just how much the story of Kamaishi means to the people of Japan. This is a special place, with spirited people, who have the soul of rugby in their DNA. Any fans coming here for the Rugby World Cup are in for a pretty magical experience.