Cars are banned downtown, a house with a garage costs more, and renewable energy is on the rise. Could Freiburg in Germany’s Black Forest region be a model for urban sustainability?

Cars are banned downtown, a house with a garage costs more, and renewable energy is on the rise. Could Freiburg in Germany’s Black Forest region be a model for urban sustainability?

By the time I met Johannes Schlögl, my tour guide for the evening, near the visitor center in Freiburg’s Old Town, I’d already clocked much of what’s made this city a sustainable epicenter: Virtually car-free cobblestone streets, wide bike lanes lining traffic-calmed streets, bike-share stations and racks installed left, right and center, and zero-waste products lining shelves at local natural food stores.

He was waiting for me, smiling broadly, and stood next to a Klimacamp tent stationed to draw attention to the climate crisis and provide a space for open exchange and climate education. I chuckled, both in awe and surprise, at the idea that in a city this committed to sustainability, concerned residents were still demonstrating to advance the city’s climate protection measures.

Measures which Schlögl would tell me more about as he led me through the vehicle-free city center; and stories, not just of ancient architecture as we sipped wine in the shadow of the magnificent Gothic-design Freiburger Münster, but how the city he calls home is one of the most sustainable in Europe. It’s a milestone that didn’t happen by accident.

On the contrary, transforming Freiburg into the sustainable beacon it is—with its passive homes (homes designed to make the most of natural light and heat), solar plants, and emphasis on public transportation—has been very intentional, and began long before Schlögl or I became passionate about clean energy or renewable resources.

“This commitment is present not since yesterday, but for several decades,” Schlögl explains. In fact, Freiburg’s forward motion started in the 1970s when city residents organized to successfully prevent the building of a nuclear power plant near the town.

There are only about 410 vehicles per 1,000 people in Freiburg; that’s 200 vehicles fewer than other major German cities. In comparison, there are 900 cars per 1,000 people in the US.

Since then, it’s been a destination driven toward innovation, from championing renewable energies like solar and wind, to reducing vehicular traffic with functional public transit and encouraging cycling—Radstation near the central transit station houses hundreds of bikes in an automated storage center—all of which has earned it the nickname, ‘Green City’.

In Freiburg, the public transit system, consisting of trams and buses, is designed so that no residence is more than 400 meters from any public transport stop—it makes the car I drove into town feel utterly irrelevant. Indeed, I didn’t use it again until it was time to leave the city and return home. And that’s the point.

In fact, the city offers incentives for locals to forego even owning one, with limited parking spaces and hefty parking fees in some neighborhoods. And those incentives seem to be working: There are only about 410 vehicles per 1,000 people in Freiburg; that’s 200 vehicles fewer than other major German cities. In comparison, there are 900 cars per 1,000 people in the US.

All of this makes Freiburg supremely easy for visitors like me to explore. Home for a few days is the energy-efficient Green City Hotel Vauban, built with passive energy systems and no single-use plastic, and just steps from a tram stop. I’ve never been more pleased to use public transit in a foreign city.

It’s clean, powered by renewable energy, goes everywhere I want to go, is easy to navigate—even as someone who manages to get on the wrong train or bus just about everywhere I go—and costs less than €3 for an hour-long pass although my hotel provides guests with a transit pass valid for their visit. And making it easy is key— even before I realized trams or biking were my only options, I intended to use the included pass.

Once we start our wander, Schlögl points out the innovative streetside Bächle (canals) which have been bringing fresh water to Old Town since at least the 11th century. He also tells me about the neighborhoods surrounding Old Town, like sustainably designed Vauban, Wiehre and Herdern with their shade trees, gardens and parks, traffic-calmed streets, access to public transport, and focus on passive construction, and many of the more recent, behind-the-scenes sustainable initiatives and innovations.

He tells me Freiburg is one of the first cities in Germany to establish an entire office dedicated to environmental protection, and that it’s been awarded a slew of prizes and accolades for everything from public transit and solar power to urban development and climate protection.

The city was one of the first to install an early warning system for smog and ozone pollution, as well as introduce pesticide bans. More recently, Freiburg announced a goal to achieve climate neutrality by 2035, an ambitious objective to generate as much energy as the city uses by expanding wind and solar power, sustainable heat supply, and public transportation options.

Rarely does a city of comparable size—think Boise, Idaho or Ghent, Belgium—have more woodland and such a diversity of landscapes, from the Black Forest—Freiburg sits on its edge—to the River Rhine.

Food and food waste come into this too. In 2022, local nurseries and elementary school cafeterias became fully vegetarian, which plays a substantial role in reducing emissions from factory farming. Residents are also very involved in policy recommendations—in fact, the Green City Office says, “Citizens’ initiatives are the driving force behind politics: They often develop new ideas and concepts with a great deal of know-how, they are involved in the political discourse on sustainable development goals, and they support us by leading the way with good ideas and examples themselves.”

Additionally there are incentives which encourage citizens to make more sustainable choices, for example encouraging parents to use cloth diapers instead of disposables, and offering discounts for residents who compost their green waste—which is often sent to wood-fueled heat and power stations where it’s fermented and converted into electricity.

“It’s really a push into the right direction, and I hope it will get more and more and even less cars and more green,” Schlögl says.

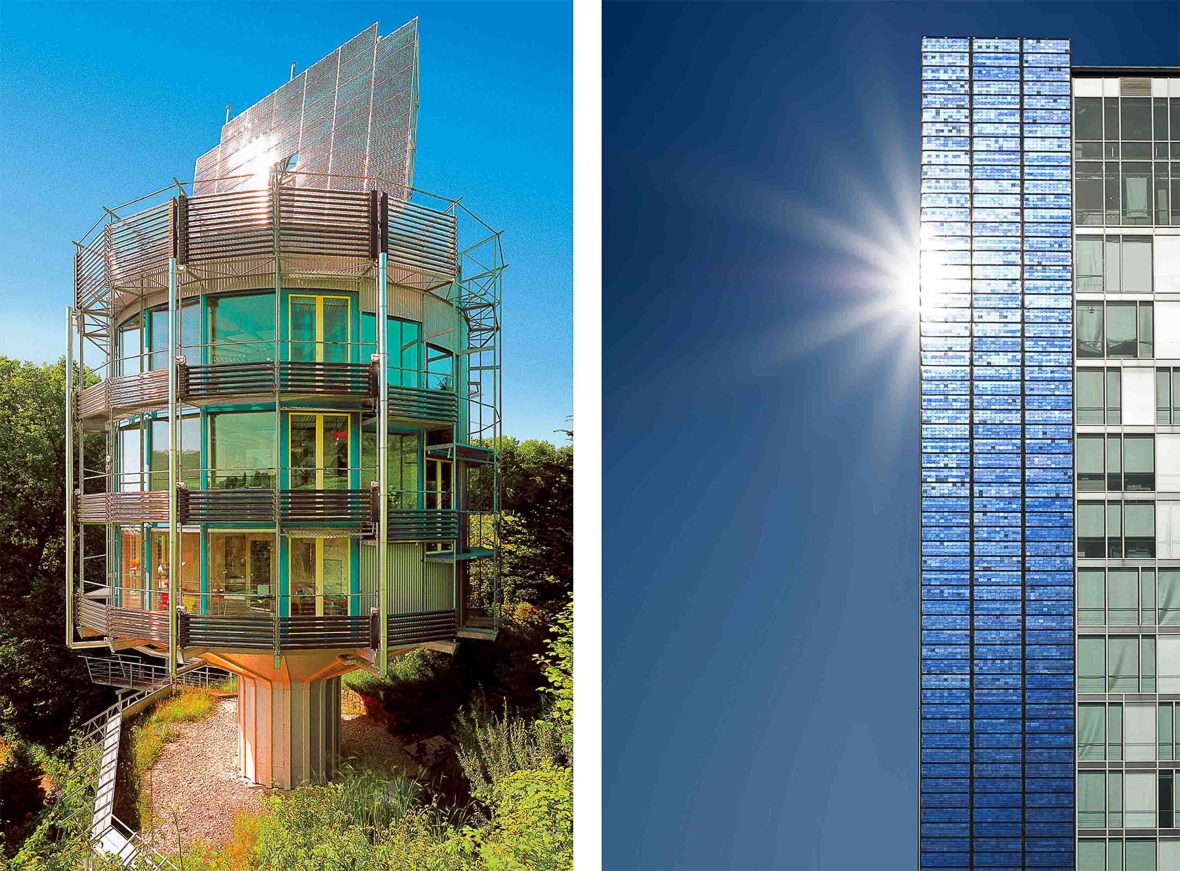

Indeed, the renewable energy sector is booming in Freiburg, though solar power is the current superstar and can be spotted everywhere. The Badenova Stadium (or Schwarzwald Stadion) is the world’s first stadium with its own solar plant; the city hall, schools, churches, homes, and even the prison have solar panels; and Freiburg is home to the world’s first energy self-sustaining solar home—the Heliotrope—and many zero-energy homes in the Vauban neighborhood, which was specifically designed to be highly energy efficient and virtually car-free.

New city administrative buildings are designed so they generate more energy than they consume, and the city is planning a new climate-neutral district that will house 16,000 people—and use the same amount or less energy than it conducts via alternative energy sources.

All of it also happens to make Freiburg a wonderful place to explore. Fewer cars on the road allows for more leisurely wandering through forested parks and cobblestone streets, accessible and efficient public transit plus bike-share programs reduce journey times, and vegan and vegetarian meal options are easier to find—increasingly important and certainly to me.

Cycling route maps show the locations of bike rental stations and there are numerous urban parks like the sprawling Schlossberg adding more green to an already ‘green city’.

Rarely does a city of comparable size—think Boise, Idaho or Ghent, Belgium—have more woodland and such a diversity of landscapes, from the Black Forest—Freiburg sits on its edge—to the River Rhine. And residents and visitors don’t need a car to enjoy outdoor adventures such as hiking and mountain biking across 450 kilometers of trails within riding distance or public transit from the city center.

For more distant destinations where a car is necessary or useful, green options are also available. “There is also a good network of car-sharing stations, which I use often when I want to go on a trip with friends on the weekend and they don’t have a bike or we share a car to go further out,” Schlögl tells me.

From high atop Schlossberg Tower, I look down over the city’s green canopies, medieval architecture and streets lined with what I know are modern energy-efficient housing, the bike-loving, sustainably-driven traveler in me wishes for just one thing: More time to explore this legitimately sustainable urban wonder.

****

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions travel publication. We are powered by, but editorially independent of, Intrepid Travel, the world’s largest travel B Corp, who help ensure Adventure.com maintains high standards of sustainability in our work and activities. You can visit our sustainability page or read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information.

Alisha McDarris is a journalist and photographer. Growing up with a love of travel and outdoor adventure, sustainability also became more important to her. Now, all three are the focus of her writing and photography work in Backpacker, Popular Science, Hemispheres, American Way, Austin Monthly, CultureMap, Eater, The New Zealand Herald, Roadtrippers and more.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: