From a late-night arrival in the Spanish city of Alcover to the final destination of a forest arts and movement retreat—all by wheelchair—Tanzila Khan shares what she learned in the most unexpected of ways.

From a late-night arrival in the Spanish city of Alcover to the final destination of a forest arts and movement retreat—all by wheelchair—Tanzila Khan shares what she learned in the most unexpected of ways.

The city centre of Alcover in Spain looked like an empty movie set. The taxi had dropped me off after struggling through mountainous terrain, dealing with cell phone signal and language issues while I searched for the exact location for the art retreat I had come to attend.

I’d always been fond of theater and use of body for expression, but this was met with resistance in Pakistan; it’s not a place where the body is a subject that’s often discussed. When this retreat opened a space for art, movement and expression, I felt I would find a space and community that would understand me and I’d go to any lengths to be there.

I stretched my body as much as the wheelchair permitted. My thoughts flitted back to that morning when I’d sat for four hours on the platform at Barcelona Sants Station, simply waiting to get accessible support to board the train. The management shrugged—and the trains left without me while I just waved.

Earlier that same morning, I had ‘walked’ to the station, appreciating the wheelchair accessibility of the streets and buses. But after waiting at the station, I finally took a taxi—which cost me eight times the price of a train ticket. I received a good math lesson by calculating the ‘disability tax’, a penalty paid by many solo wheelchair travelers like myself, all because of loopholes in accessibility policies overlooked by policymakers. Good policies for the disabled population exist—but they have very limited implementation.

In Alcover, I found a lively café filled with what appeared to be regular customers and I ordered coffee.

The eyes around me watched my every move. I was the stranger; the intruder or the guest in their town. But despite the mystery in the air, every gaze offered a sense of concern and care.

I counted everything peculiar that they can wonder about me, starting from my hijab to my powered wheelchair. But the only person confident enough to speak to me was a six-year-old boy who came and shook hands. I played with him, and his mother invited me to her table where she sat with her sister and father.

They offered me their beer. I offered them my coffee.

“Backpacker?” the mother asked me in broken English.

“No, a traveler. I am here for a retreat,” I replied.

It was getting dark. I hugged and kissed the mother and child goodbye. After a few minutes of dodging winding roads and traffic, I could see my phone battery signaling red. My breath quickened and loose strings of hair fell on my forehead.

I saw two boys ahead, and raised my hand in defeat. They told me it was impossible to reach the retreat venue on foot, especially in such darkness. They introduced themselves as Mon and Luis.

The size and magnitude of the forest was irrelevant to me. My focus was on every inch of it seemingly covered in rocks, sticks and leaves, and how I’d navigate it.

Mon wasn’t much of a talker, but he pushed my wheelchair manually. Luis ordered a taxi. They stood next to me in silence, waiting for the taxi. They only left after they had made sure I was in it, and had directed the driver thoroughly on where to take me.

My eyes welled with tears of gratitude at this kindness. A kindness that forms part of an underground ‘system’ of accessibility that thrives on community beyond language, religion, class or gender. Or policy.

The next morning, I met with other fellows at the retreat from across the world who had come to learn the art of movement. The size and magnitude of the forest was irrelevant to me. My focus was on every inch of it seemingly covered in rocks, sticks and leaves, and how I’d navigate it.

When I looked up, I saw a vast mountainous forest overlooking the city of Alcover. On one occasion, I had to park myself under a tree, out of breath from my exertions. My body was sore. I wondered if the forest would be kind—or devour me in the next four days?

I removed the sticks stuck in my wheels, and before I joined the rest of the group, I felt the tree sway with the wind and a leaf fell on my face. I planted a kiss on it as a greeting and whispered, “Salaam!”

The next few days were filled with chanting, meditation, Georgian folk songs and conversations on love. We helped each other. Contrary to real life, it was easier to find partners in workshops and dance without judgement here.

Moving my wheelchair to reach the venue, eating area before retiring to use the bathroom exhausted my body. I named the path to my cottage, ‘the road to salvation’—which made everyone chuckle.

I danced and moved and occupied space as much as my heart wanted, but also depending on how much ‘battery’ I had. We painted with twigs and learned to create rituals. My wheelchair moved with the rhythm of the forest and left wheelchair tracks, carving its own map here.

One day, during a Tantric and Shamanic Art session with former-model-turned-art-teacher Mahara Mckay, I stepped down from my wheelchair and felt the earth for the first time. The hug felt hard and prickly but I thanked the earth for helping me find accessibility even in this forest.

Moving my wheelchair to reach the venue, the eating area and to the bathroom before retiring for the evening exhausted my body. I named the path to my cottage, ‘the road to salvation’—which made everyone chuckle. The people around me helped carry my wheelchair up and down and often brought me food. On one occasion, I was escorted by five men down a steep hill to reach the bamboo house. We all agreed that this exercise was indeed a lesson on co-existing.

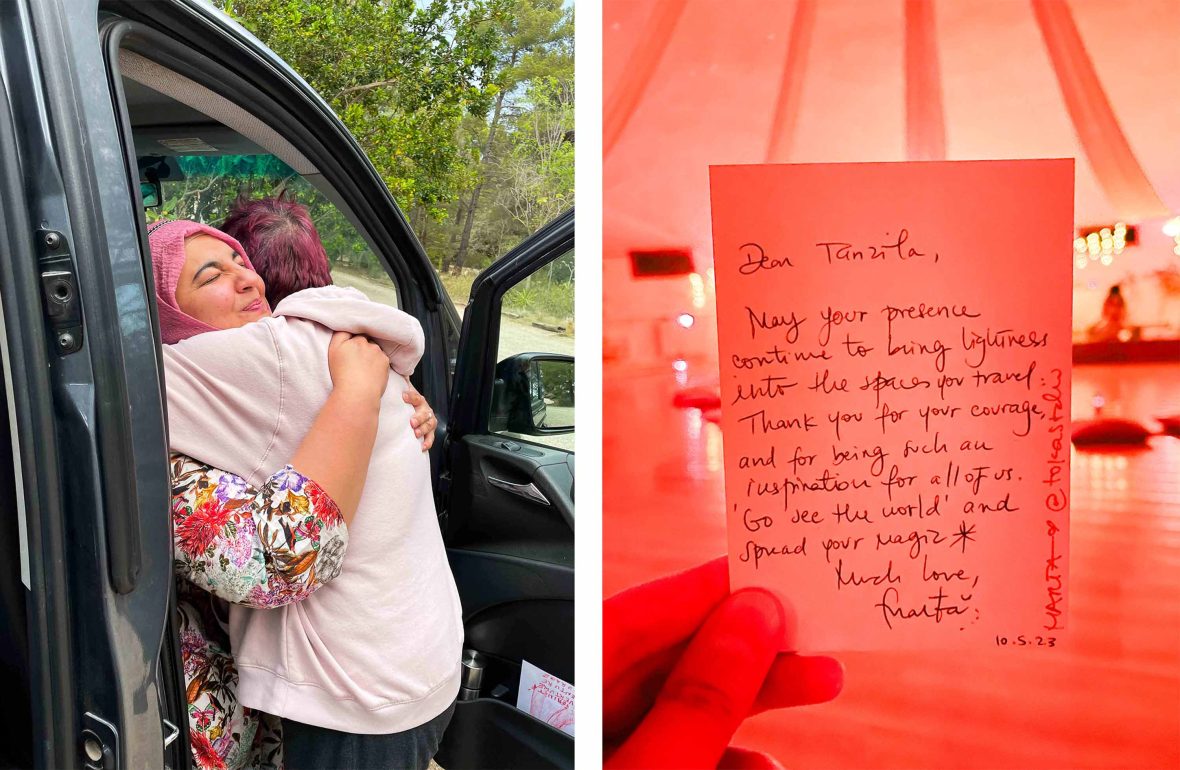

On the last day, I went back to my spot under the tree to enjoy the blanket of the warm sun. I reflected on the days of the retreat, on my sore body from the movement exercises, the stories that I heard about pain, love, suffering and trauma. And then I looked at the worn-out wheels of my wheelchair. I guess we were two participants all along.

When the retreat came to end, to my surprise, I did not feel dread taking the journey back. I did not fear getting lost or stuck. Because I now knew that my tracks too belonged to every rock and stick here.

***

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions publication, and we are working to reduce our carbon emissions where possible. Emissions generated by the movements of our staff and contributors are carbon offset through our parent company, Intrepid. You can visit our sustainability page and read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information. While we take our commitment to people and planet seriously, we acknowledge that we still have plenty of work to do, and we welcome all feedback and suggestions from our readers. You can contact us anytime at hello@adventure.com. Please allow up to one week for a response

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: