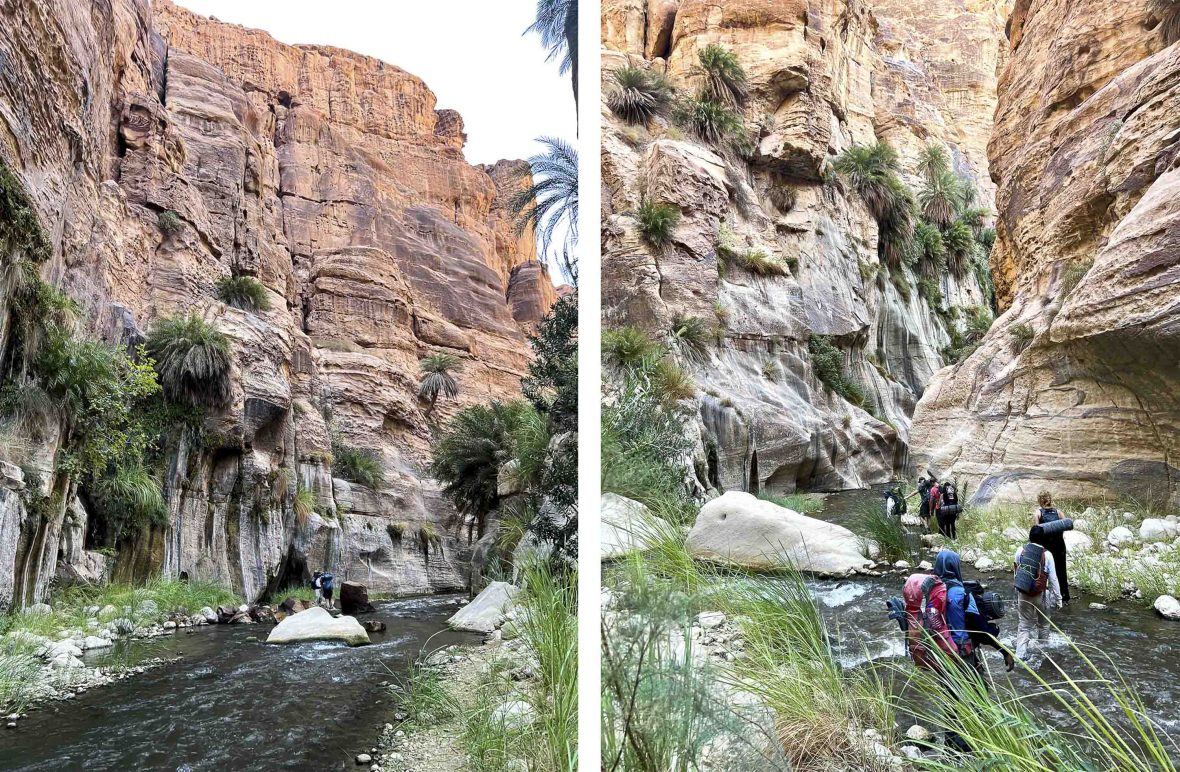

It’s one of Jordan’s most unusual treks—where you wade, jump and scramble inside Wadi al-Hasa. With her feet in water 80 percent of the time, photographer Lisa Young keeps her hands and camera dry as she captures this fascinating, and fun, trek.

It’s one of Jordan’s most unusual treks—where you wade, jump and scramble inside Wadi al-Hasa. With her feet in water 80 percent of the time, photographer Lisa Young keeps her hands and camera dry as she captures this fascinating, and fun, trek.

We enter the water through a biblical setting of bulrushes and razor-sharp reeds, which dominate the start of the Wadi al-Hasa trek. I make the mistake of grabbing the blade-like reeds to keep my balance, and they slice into my sweaty hands, making a giant stinging paper cut.

The first mile of the trek is open; there’s no shade from the sun until you reach the canyon walls. The novelty of being in water brings out the children in us and we kick about in the riverbed, laughing and splashing each other; the dousing is welcomed. I stop to fill my baseball cap with wadi water and pour it over my head, a ritual I’d practice religiously throughout the trek. “I personally love this part of the trek, but some find it uncomfortable,” our guide Munther tells us. “The hardest part is the start because we are not in the canyon yet and the sun is so strong.”

It was September 2022 when I joined a small group of friends for a two-day hike through Wadi al-Hasa with our experienced TREKS JORDAN guides, Munther Al-Titi and Mohammad Al-Zayadeen. Mohammad was actually the first person to trek the iconic Jordan Trail (which Wadi al-Hasa is separate from), a 420-mile route stretching the whole length of the country, from Um Qais in the north to Aqaba in the south, and created by 40 volunteers who formalized the trail over 20 years.

Scouting for the Jordan Trail started in 2000. It officially opened in 2016, when our guide, Mohammad Al-Zayadeen and his cousin, Mohammad Homran, were the first people to trek the entire route. They did it in just 25 days, due in part to taking on two day’s-worth of the route’s daily sections at a time.

“I was walking with my goats in Wadi Al-Haidan where the Jordan Trail passes when I saw the young volunteers scouting out the trail,” Mohammad tells me. “They told me what they were planning and I had the idea of being the first person to walk the trail. My cousin agreed to join me, making us the first two people to walk the new trail from north to south Jordan. This experience allowed me to fully explore Jordan, and get out of the circle I was in. It was easy for us because we live the life of shepherds and are used to dealing with nature.”

Our group was already acclimatized to Jordan’s autumn heat as we had trekked the first section of the Jordan Trail a few days earlier in the country’s northern region, close to the borders with Syria and Israel, across parched agricultural land colored every shade of brown. There, goat herders drove their flocks across baked, rocky hillsides; only the occasional olive plantation added a touch of green to the palette.

As we progress deeper into the canyon, the shade of its ancient walls offer relief from the sun. The occasional starling and kingfisher add a touch of color to the otherwise mostly rocky environment. The further we go in, the narrower the canyon becomes, making the water run deeper and faster.

We had spent our evenings eating with local Syrian and Jordanian families, seated on the floor on large cushions around a huge, low-set table. We tucked into the national dish, mansaf, lamb cooked in fermented yogurt and served with rice and flatbread. We tried maqluba, a meat, rice and fried vegetable dish cooked in a pot and then turned upside down before serving (maqluba means “upside-down’ in Arabic). There was also makmoura, in which layers of dough, chicken, onion and spices are baked and repeatedly stacked like a layered pie, then placed in the center of the table so it’s within arm’s reach of everyone.

That night, we stayed at Beit Al Baraka, a comfortable local guesthouse, with rooftop views of the Golan Heights in Israel, the Sea of Galilee and Syria in the distance. Breakfast was a feast of spicy shakshuka (baked eggs with tomato, and cumin), manakish (a baked dough topped with cheese and thyme) and a spread of bread, fruit, olives, cheese, jams and yogurt.

For the Wadi al-Hasa trek, we start from Tafilah, a two-hour drive from the capital, Amman, on a barren, dusty roadside just south of the town. There’s no shelter from the 95°F sun. After scrambling over rocks for a mile, we follow a well-used goat trail to the wadi, to begin the slow descent to our destination, 1,300 feet below sea level.

The start of the trek is not too challenging; there are no dangerous predators lurking in the water, but wobbly and slippery rocks underfoot threaten to unbalance anyone who steps on them.

A wadi generally means a ravine that is dry, except in the rainy season. But Wadi al-Hasa’s water comes from an underground system called the Hasa drainage, which collects rainfall from the desert and channels it to the wadi.

The 25-mile Wadi al-Hasa is mentioned in the Old Testament as the Valley of Zered, where the Israelites ended their 38 years in the wilderness. Once a natural border between two Iron Age kingdoms, Moab and Edom, its present-day location lies between the towns of Karak and Tafilah, and the wadi can be trekked in either direction.

Temperatures in the wadi range between 41-59°F in winter, with spring and fall temperatures at 77-86°F. Summer is hotter, with temperatures hovering between 104 and 113°F. Needless to say, a hat, sunblock and sunglasses are essential for our September trek.

We would eventually cover 24 miles in total (12 miles on each of the two days), zigzagging our way through the wadi, in and out of the mostly shallow stream, but clambering over boulders when the water got too fast or too deep.

I ask our guides about emergency plans, should someone get really injured. “I carry a satellite phone and will call the civil defense if someone needs evacuation,” Munther tells me. “They will find us, day or night.”

We carry our own individual lunch packs (vegetarian, as carrying meat in the heat isn’t ideal), as well as our two-person tents to keep mosquitoes at bay by night, and ground mats for added comfort.

As we progress deeper into the canyon, the shade of its ancient walls offers relief from the sun. The occasional starling and kingfisher add a touch of color to the otherwise mostly rocky environment. The further we go in, the narrower the canyon becomes, making the water run deeper and slightly faster… the flow is not quite strong enough to knock someone over. The colors of the rockface are spectacular; the deep, red, earthy tones are a contrast to the bright green plants that cling to the cliffs.

I see at least five shooting stars through the tent’s mesh, while satellites move eerily across the skies and Mars shines bright orange throughout the night. A rustling bush ignited my imagination; perhaps a fox or a hyena, or even a rare wolf we’d been told about.

Hanging plants and shrubs dangle from the rockface where we drink the natural spring water directly from the wadi. It’s too shallow to swim, so we luxuriate in shallow pools, and shower under a refreshing natural spring, a cooling relief from the heat.

At the end of the first long, hot day, we set up camp on a large ledge away from the water, while our guides light a fire and prepare an energizing dinner of rice and vegetables in a tomato sauce, prepared with olive oil and spices. The only light in the camp comes from the fire, the moon, and the stars.

Sitting around the fire, I ask Munther if he has a favorite trek. “I love Wadi Rum,” he replies. “The desert landscapes are wild and colorful, and you don’t see anyone on the trail for four or five days.”

“There are a lot of great trails in this country other than the famous Jordan trail. We do a lot of scouting, especially in Wadi Arraba in the south where the virgin land is great for trekking.”

Being in water so much of the time wrecks footwear. Even the toughest, famous-name boots suffer. We have to make sure our tents, food, cameras, phones, and everything else we own are well-waterproofed in a dry bag along with our sleep clothes and flip-flops for camp; otherwise, we’d spend the evening in wet boots.

I see at least five shooting stars that night through the tent’s mesh, while satellites move eerily across the skies and Mars shines bright orange throughout the night. A rustling bush ignited my imagination; perhaps a fox or a hyena, or even one of the rare wolves we’d been told about.

The trek is not especially challenging, but during the day, I had slipped off a rock and twisted my knee. The following morning, I decided to take it easy. The rest of the group set off down the wadi with Munther, leaving Mohammad to travel with me at a pace my knee would tolerate.

Who would have thought my injury would turn out to be a highlight of my trip? I’m suddenly on my own personalized trek, with unlimited time to stop and take photos, and in the company of Mohammad, a caring, patient soul—the dream guide. To top it all off, every now and then, he takes out a flute from his sun-bleached backpack and plays tunes, while standing in the middle of the water-filled wadi.

It is a reminder of one of the highlights of traveling: Talking to and spending time with people in the country you’re visiting. I listen to Mohammad’s stories about his family, his life in the mountains taking care of his mother, and his passion—looking after his precious goats. He says while he has trekked the Jordan Trail many times, for him, it’s a walk in the park compared to chasing after his flock.

The scenery on that second day seems even more sublime, with bigger rocks to maneuver around. We walk below huge boulders the size of small houses, which have fallen hundreds of feet from the top of the rim and wedged themselves between the wadi’s walls. As we close in on the end of the trek, it turns out that we aren’t even too far behind the rest of the group.

Trekking Wadi al-Hasa has been a fascinating, elemental experience of water, rock, and sun, in a place that nature has carved out over millennia. Forever in my memories are the relentless heat of the sun against the cool shade of the canyon walls, the clarity of the star-filled night sky, the soundtrack of the ever-flowing water, and of course, of Mohammad—knee-deep in the river with the haunting melodies of his flute.

____

The writer traveled with Millis Potter, specialists in bespoke travel itineraries in the Middle East and Asia, and hiked with Jordanian trekking specialists, TREKS.

***

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions publication, and we are working to reduce our carbon emissions where possible. Emissions generated by the movements of our staff and contributors are carbon offset through our parent company, Intrepid. You can visit our sustainability page and read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information. While we take our commitment to people and planet seriously, we acknowledge that we still have plenty of work to do, and we welcome all feedback and suggestions from our readers. You can contact us anytime at hello@adventure.com. Please allow up to one week for a response.

Lisa Young is a photographer and travel writer whose work has appeared in The Telegraph, The Times, Wanderlust, Warner Bros, NGT, Guardian, Observer, Vanity Fair, and Country & Town House. She often spends weeks living in unusual places to experience daily life of a remote culture, and gain trust from her subjects. Specializing in the Polar regions, she's also covered stories about cultural tribes, Indigenous tourism, and development projects.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: